Why Time Limits Don’t Work (And What To Do Instead in 2026)

If you’ve ever tried to reduce your screen time, there is a high probability you already tried time limits. 30 minutes a day on Instagram. 1 hour on TikTok. It sounds like the most reasonable solution in the world. If an app steals too much time, you simply need to cap the time. Right?

Ideas & Tips

12 janv. 2026

5 min

And yet, if you are reading this, there is a good chance you have also felt the downside: time limits are easy to ignore, frustrating when they hit, and oddly hard to maintain without eventually rebelling against them.

In this article, I will explain you why time limits often fail, what they get wrong about habits, and what to do instead in 2026 if you want a calmer, more sustainable relationship with your phone.

But before we continue, it might be time for me to introduce myself! I’m Thomas, co-founder of Jomo. Over the last 4 years, I’ve spent most of my time thinking about screen time habits and building an app that’s used by more than 250,000 people.

Based on our most recent 100,000 users, the average Jomo user reduces their daily screen time by about 1 hour and 39 minutes.

Not because they suddenly gain superhuman willpower, but because they change a few small habits that make mindless scrolling harder and intentional phone use easier.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Time Limits

Time limits are built on a simple assumption: screen time is mainly a quantity problem. Too many minutes. Too many hours. So the solution is to restrict the quantity.

But most screen habits are not primarily about time. They are about automaticity.

The real problem is not “I spend 60 minutes on Instagram”. The real problem is “I open Instagram without choosing to, and I stay longer than I intended”.

A bad habit usually starts with a trigger: boredom, stress, anxiety, procrastination, loneliness, or just a tiny gap in your day. You pick up your phone, open an app, and you are already in it before you have made a real decision.

By the time a time limit kicks in, the habit has already taken over. Your attention is captured. Your brain is engaged. You are in the middle of scrolling when suddenly the app closes or locks.

That moment rarely feels like support. It feels like interruption. Like being pulled away from something your brain is now invested in, even if it is not even that enjoyable.

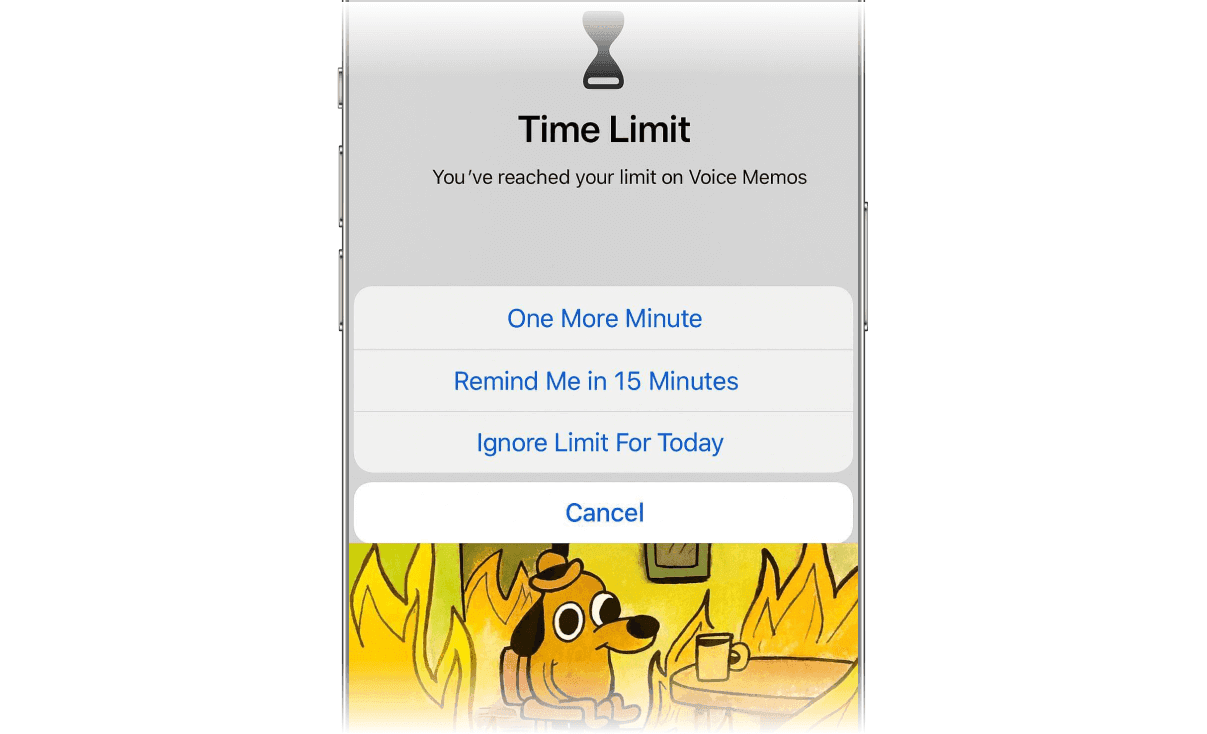

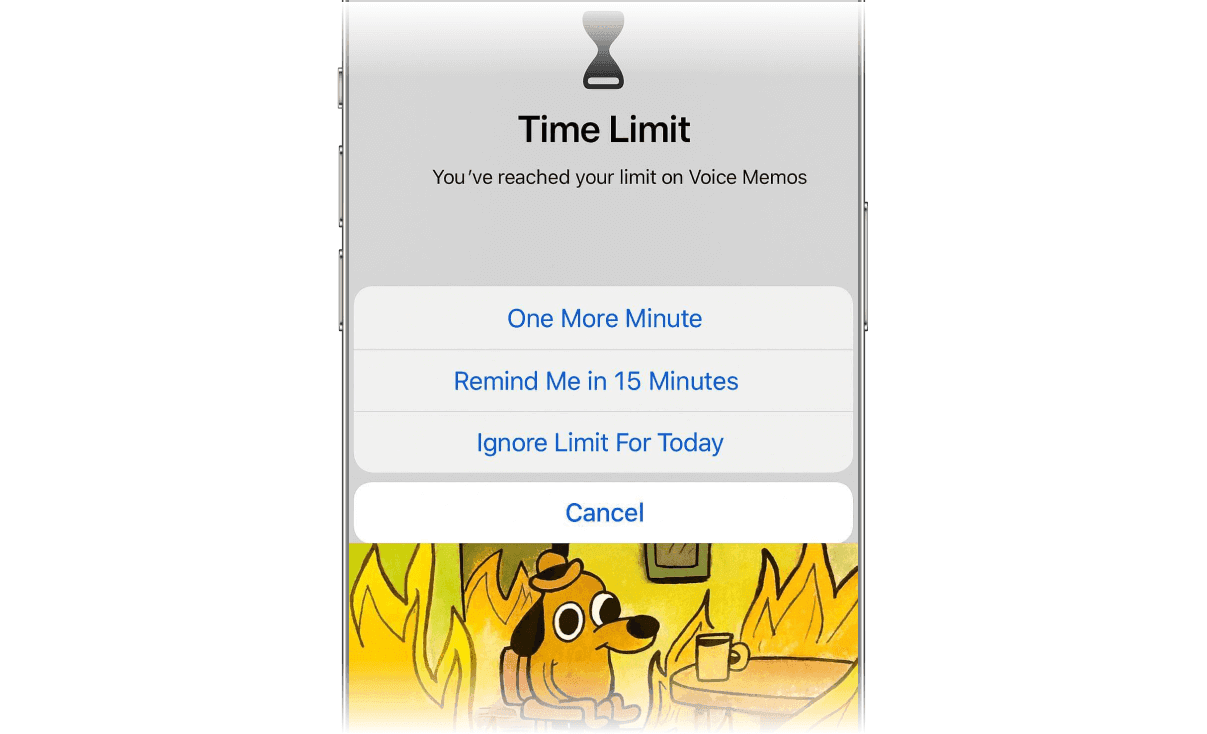

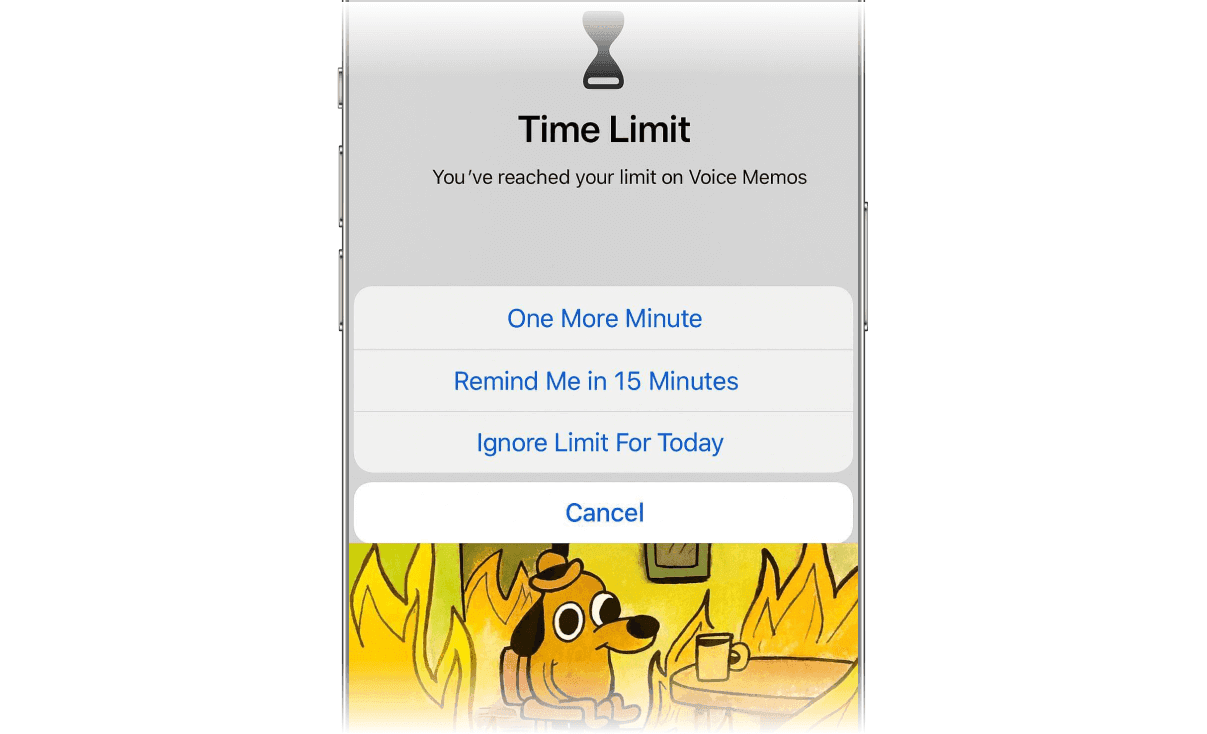

You when your time limit hits.

So the limit creates friction, but it creates friction too late. And when friction arrives at the peak of craving, the most common outcome is not “Great, I’m done”. It is “Remind me in 15 minutes”.

This is why time limits so often turn into a strange cycle: you set them with good intentions, you hit them in the middle of a dopamine loop, you override them, and then you feel like you failed.

Time Limits Fight the Wrong Part of the Habit Loop

If you have ever tried to change any habit, you have probably noticed a pattern: habits are not changed at the end. They are changed at the start.

A habit has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The beginning is the trigger

The middle is the behavior

The end is the reward

Time limits only target the end, and only after the behavior has already been running for a while. They do almost nothing to change the trigger, and they do not help you enter the app with intention.

That is why someone can “successfully” respect a time limit and still feel like their screen habit is unhealthy. You can spend only 20 minutes on an app, but if those 20 minutes were compulsive, automatic, and triggered by stress, the habit is still training the same neural pathway.

In other words, you reduced minutes, but you did not improve the habit.

Why Time Limits Make You Rebel (Even If You Set Them Yourself)

There is also a psychological reason time limits fail: they feel controlling.

Even if you are the one who created the rule, the rule behaves like an external authority. It does not care about context. It applies the same way when you are bored, stressed, lonely, or genuinely using an app for something meaningful.

Rigid rules tend to break under real life. And once you have broken them a few times, your brain learns a new habit: overriding your own boundaries.

This is one of the hidden problems with time limits. They do not only fail to fix the original habit. They can teach you a second habit: “Rules don’t matter when I really want something.”

When we designed Jomo, one of our guiding principles was simple: if a system makes you feel trapped, you will eventually escape it.

The “Binge Before the Cutoff” Effect

Time limits can also change how you use apps in a weird way.

Many people end up cramming the same amount of stimulation into a smaller window. They scroll faster. They binge right before the cutoff. They treat the app like a last-chance buffet.

This is not a moral failure. It is a predictable response to scarcity. When access becomes limited, the brain wants to “get it while it’s available.” So you might reduce your minutes, but you increase intensity. And intensity is often what leaves you feeling drained.

And yet, if you are reading this, there is a good chance you have also felt the downside: time limits are easy to ignore, frustrating when they hit, and oddly hard to maintain without eventually rebelling against them.

In this article, I will explain you why time limits often fail, what they get wrong about habits, and what to do instead in 2026 if you want a calmer, more sustainable relationship with your phone.

But before we continue, it might be time for me to introduce myself! I’m Thomas, co-founder of Jomo. Over the last 4 years, I’ve spent most of my time thinking about screen time habits and building an app that’s used by more than 250,000 people.

Based on our most recent 100,000 users, the average Jomo user reduces their daily screen time by about 1 hour and 39 minutes.

Not because they suddenly gain superhuman willpower, but because they change a few small habits that make mindless scrolling harder and intentional phone use easier.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Time Limits

Time limits are built on a simple assumption: screen time is mainly a quantity problem. Too many minutes. Too many hours. So the solution is to restrict the quantity.

But most screen habits are not primarily about time. They are about automaticity.

The real problem is not “I spend 60 minutes on Instagram”. The real problem is “I open Instagram without choosing to, and I stay longer than I intended”.

A bad habit usually starts with a trigger: boredom, stress, anxiety, procrastination, loneliness, or just a tiny gap in your day. You pick up your phone, open an app, and you are already in it before you have made a real decision.

By the time a time limit kicks in, the habit has already taken over. Your attention is captured. Your brain is engaged. You are in the middle of scrolling when suddenly the app closes or locks.

That moment rarely feels like support. It feels like interruption. Like being pulled away from something your brain is now invested in, even if it is not even that enjoyable.

You when your time limit hits.

So the limit creates friction, but it creates friction too late. And when friction arrives at the peak of craving, the most common outcome is not “Great, I’m done”. It is “Remind me in 15 minutes”.

This is why time limits so often turn into a strange cycle: you set them with good intentions, you hit them in the middle of a dopamine loop, you override them, and then you feel like you failed.

Time Limits Fight the Wrong Part of the Habit Loop

If you have ever tried to change any habit, you have probably noticed a pattern: habits are not changed at the end. They are changed at the start.

A habit has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The beginning is the trigger

The middle is the behavior

The end is the reward

Time limits only target the end, and only after the behavior has already been running for a while. They do almost nothing to change the trigger, and they do not help you enter the app with intention.

That is why someone can “successfully” respect a time limit and still feel like their screen habit is unhealthy. You can spend only 20 minutes on an app, but if those 20 minutes were compulsive, automatic, and triggered by stress, the habit is still training the same neural pathway.

In other words, you reduced minutes, but you did not improve the habit.

Why Time Limits Make You Rebel (Even If You Set Them Yourself)

There is also a psychological reason time limits fail: they feel controlling.

Even if you are the one who created the rule, the rule behaves like an external authority. It does not care about context. It applies the same way when you are bored, stressed, lonely, or genuinely using an app for something meaningful.

Rigid rules tend to break under real life. And once you have broken them a few times, your brain learns a new habit: overriding your own boundaries.

This is one of the hidden problems with time limits. They do not only fail to fix the original habit. They can teach you a second habit: “Rules don’t matter when I really want something.”

When we designed Jomo, one of our guiding principles was simple: if a system makes you feel trapped, you will eventually escape it.

The “Binge Before the Cutoff” Effect

Time limits can also change how you use apps in a weird way.

Many people end up cramming the same amount of stimulation into a smaller window. They scroll faster. They binge right before the cutoff. They treat the app like a last-chance buffet.

This is not a moral failure. It is a predictable response to scarcity. When access becomes limited, the brain wants to “get it while it’s available.” So you might reduce your minutes, but you increase intensity. And intensity is often what leaves you feeling drained.

And yet, if you are reading this, there is a good chance you have also felt the downside: time limits are easy to ignore, frustrating when they hit, and oddly hard to maintain without eventually rebelling against them.

In this article, I will explain you why time limits often fail, what they get wrong about habits, and what to do instead in 2026 if you want a calmer, more sustainable relationship with your phone.

But before we continue, it might be time for me to introduce myself! I’m Thomas, co-founder of Jomo. Over the last 4 years, I’ve spent most of my time thinking about screen time habits and building an app that’s used by more than 250,000 people.

Based on our most recent 100,000 users, the average Jomo user reduces their daily screen time by about 1 hour and 39 minutes.

Not because they suddenly gain superhuman willpower, but because they change a few small habits that make mindless scrolling harder and intentional phone use easier.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Time Limits

Time limits are built on a simple assumption: screen time is mainly a quantity problem. Too many minutes. Too many hours. So the solution is to restrict the quantity.

But most screen habits are not primarily about time. They are about automaticity.

The real problem is not “I spend 60 minutes on Instagram”. The real problem is “I open Instagram without choosing to, and I stay longer than I intended”.

A bad habit usually starts with a trigger: boredom, stress, anxiety, procrastination, loneliness, or just a tiny gap in your day. You pick up your phone, open an app, and you are already in it before you have made a real decision.

By the time a time limit kicks in, the habit has already taken over. Your attention is captured. Your brain is engaged. You are in the middle of scrolling when suddenly the app closes or locks.

That moment rarely feels like support. It feels like interruption. Like being pulled away from something your brain is now invested in, even if it is not even that enjoyable.

You when your time limit hits.

So the limit creates friction, but it creates friction too late. And when friction arrives at the peak of craving, the most common outcome is not “Great, I’m done”. It is “Remind me in 15 minutes”.

This is why time limits so often turn into a strange cycle: you set them with good intentions, you hit them in the middle of a dopamine loop, you override them, and then you feel like you failed.

Time Limits Fight the Wrong Part of the Habit Loop

If you have ever tried to change any habit, you have probably noticed a pattern: habits are not changed at the end. They are changed at the start.

A habit has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The beginning is the trigger

The middle is the behavior

The end is the reward

Time limits only target the end, and only after the behavior has already been running for a while. They do almost nothing to change the trigger, and they do not help you enter the app with intention.

That is why someone can “successfully” respect a time limit and still feel like their screen habit is unhealthy. You can spend only 20 minutes on an app, but if those 20 minutes were compulsive, automatic, and triggered by stress, the habit is still training the same neural pathway.

In other words, you reduced minutes, but you did not improve the habit.

Why Time Limits Make You Rebel (Even If You Set Them Yourself)

There is also a psychological reason time limits fail: they feel controlling.

Even if you are the one who created the rule, the rule behaves like an external authority. It does not care about context. It applies the same way when you are bored, stressed, lonely, or genuinely using an app for something meaningful.

Rigid rules tend to break under real life. And once you have broken them a few times, your brain learns a new habit: overriding your own boundaries.

This is one of the hidden problems with time limits. They do not only fail to fix the original habit. They can teach you a second habit: “Rules don’t matter when I really want something.”

When we designed Jomo, one of our guiding principles was simple: if a system makes you feel trapped, you will eventually escape it.

The “Binge Before the Cutoff” Effect

Time limits can also change how you use apps in a weird way.

Many people end up cramming the same amount of stimulation into a smaller window. They scroll faster. They binge right before the cutoff. They treat the app like a last-chance buffet.

This is not a moral failure. It is a predictable response to scarcity. When access becomes limited, the brain wants to “get it while it’s available.” So you might reduce your minutes, but you increase intensity. And intensity is often what leaves you feeling drained.

Votre téléphone, vos règles. Bloquez ce que vous voulez, quand vous voulez.

Pour 30 minutes

Tous les jours

Le week-end

Pendant les heures de travail

De 22h à 8h

Pour 7 jours

Tout le temps

Votre téléphone, vos règles. Bloquez ce que vous voulez, quand vous voulez.

Pour 30 minutes

Tous les jours

Le week-end

Pendant les heures de travail

De 22h à 8h

Pour 7 jours

Tout le temps

Votre téléphone, vos règles. Bloquez ce que vous voulez, quand vous voulez.

Pour 30 minutes

Tous les jours

Le week-end

Pendant les heures de travail

De 22h à 8h

Pour 7 jours

Tout le temps

What Works Better Than Time Limits in 2026

If time limits are not optimal, what is? The short answer is: friction and intention. You want to change your screen habit upstream, before it becomes automatic.

Concretely, this means shifting away from “I can use Instagram for 30 minutes a day” and toward:

Limiting the number of openings

Adding a tiny speed bump before each opening

Deciding how long you want to stay before entering

For example:

3 openings per day of Instagram

10 minutes each

with a small action before opening (waiting, breathing, writing your reason for using the app)

Let’s break down why this approach work best.

1. Friction, But At The Right Moment

Friction is one of the most powerful tools in habit design.

In simple terms, friction is effort. The harder something is to do, the less likely it becomes automatic. Over the past decade, phones have removed almost all friction. Your phone is always with you. It unlocks instantly. Apps open in milliseconds. Feeds never end. Notifications pull you in without permission.

So the best way to change a screen habit is to reintroduce small friction at the start of the loop, not at the end.

Instead of blocking you after 30 minutes, you add a small pause before opening the app. That pause can be a decision, a short wait, a breath, a reminder, or a simple question: “Do I actually want to open this right now?”

That moment of friction sounds tiny, but it completely changes the habit. It shifts you from autopilot to agency.

In Jomo, this is one of the core ideas: adding intentional friction before opening distracting apps, rather than only punishing you after you have already fallen into the scroll.

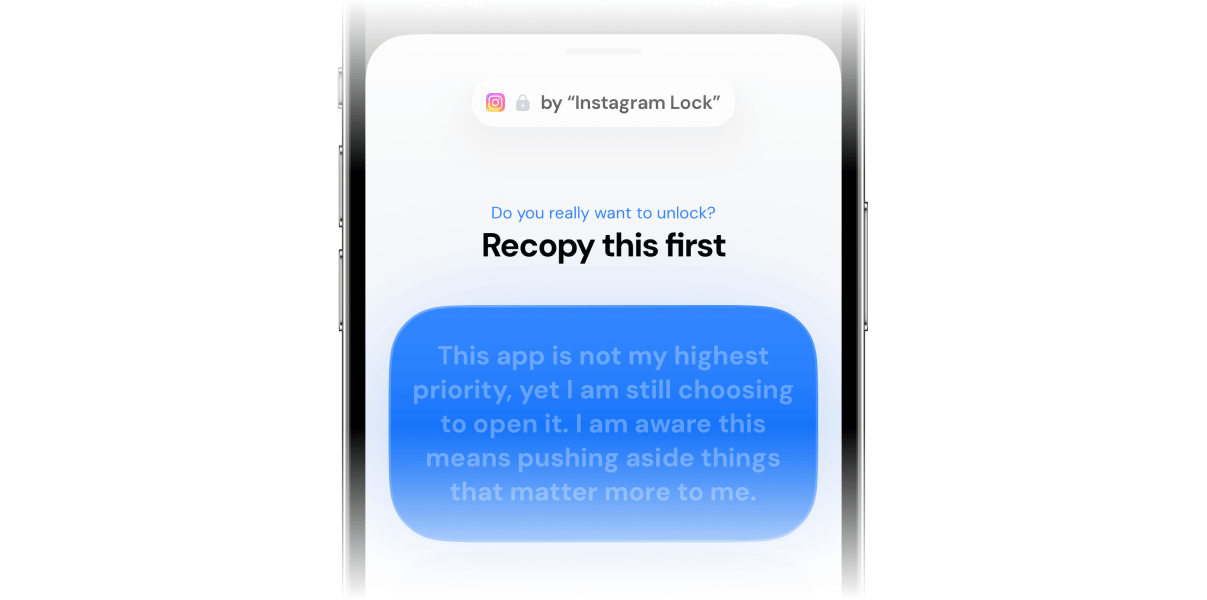

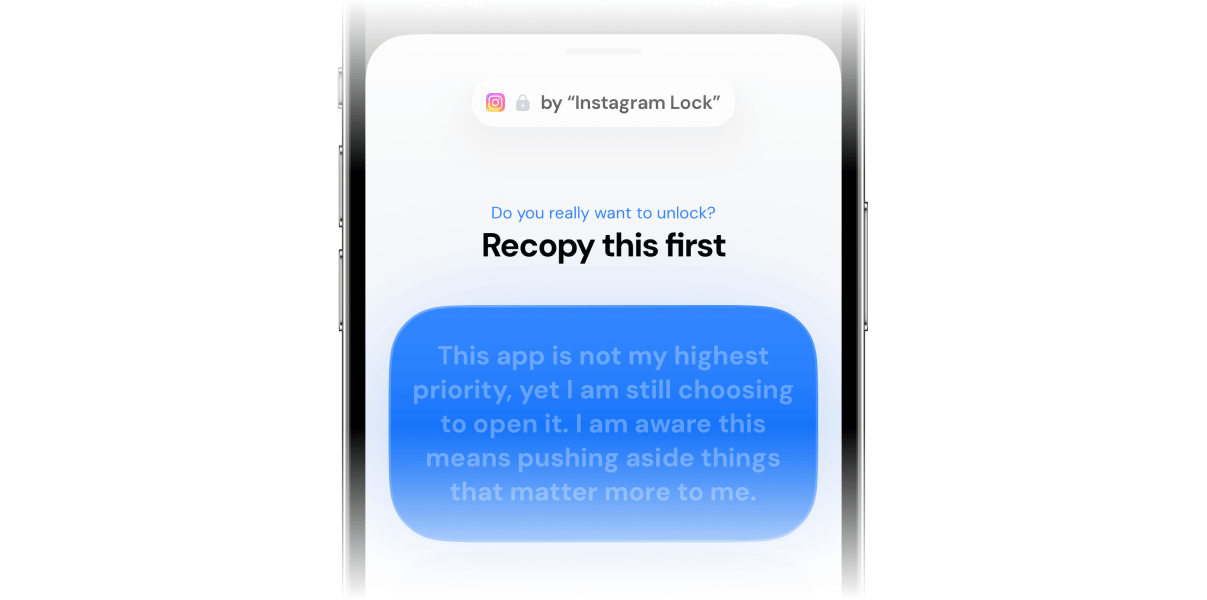

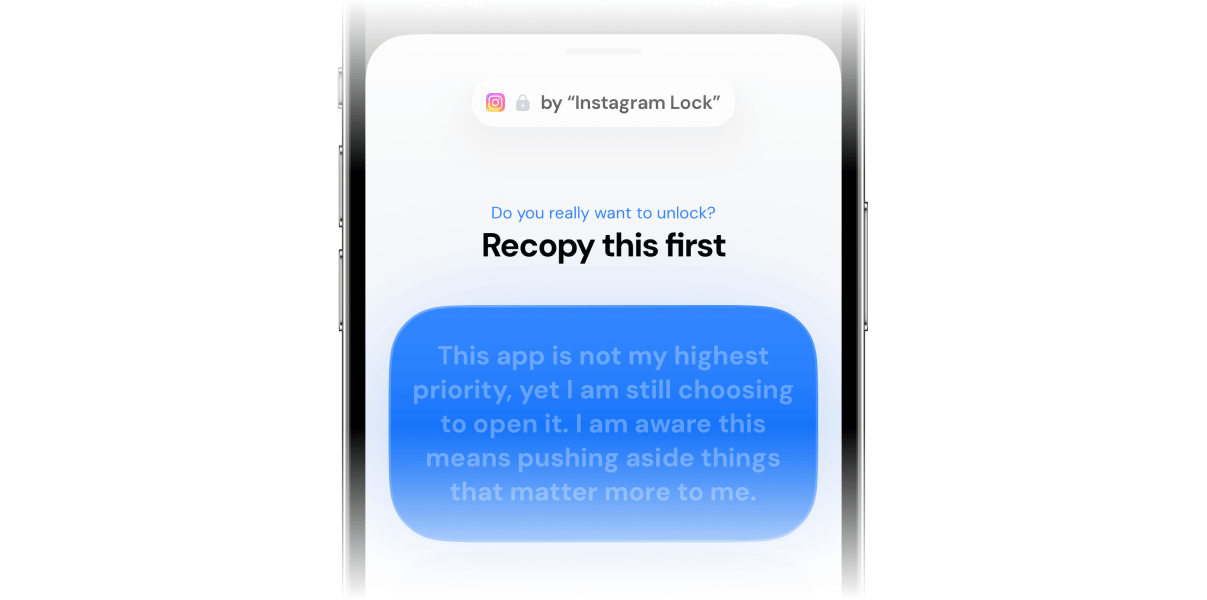

What if you had to recopy this text before opening Instagram? You'd actually think twice about it.

2. Intentional Sessions Instead Of Compulsive Use

Another big shift is moving from compulsive use to intentional sessions.

A lot of screen time is not chosen. It is compulsive. A few minutes here, a few minutes there, repeated all day. It feels harmless because each session is short, but the habit becomes constant.

A healthier screen habit often comes from doing the opposite: fewer openings, more intention.

For example, instead of “I can use Instagram for 30 minutes per day” you move to “I can open Instagram three times per day, and I choose how long each session will be”.

This one change is surprisingly effective because it forces you to be conscious at the exact moment the habit usually runs unconsciously.

Jomo is built to support this style of use. Not just time limits, but intentional sessions and controlled openings, so your screen time habits becomes something you choose, not something that happens to you.

3. Awareness Beats Restriction

The last principle is awareness.

A lot of people think they need stricter rules. What they actually need is better awareness. Not in the form of shame or obsessive tracking, but in the form of small check-ins that make the habit visible again.

When you add friction and intentional entry, awareness shows up naturally. You start noticing patterns: which apps you open when you are stressed, which time of day triggers your worst scrolling habit, which moments are actually fine.

This is how many Jomo users end up reducing screen time. They stop hitting their limits because they are no longer entering apps mindlessly. The habit changes shape before the minutes even matter.

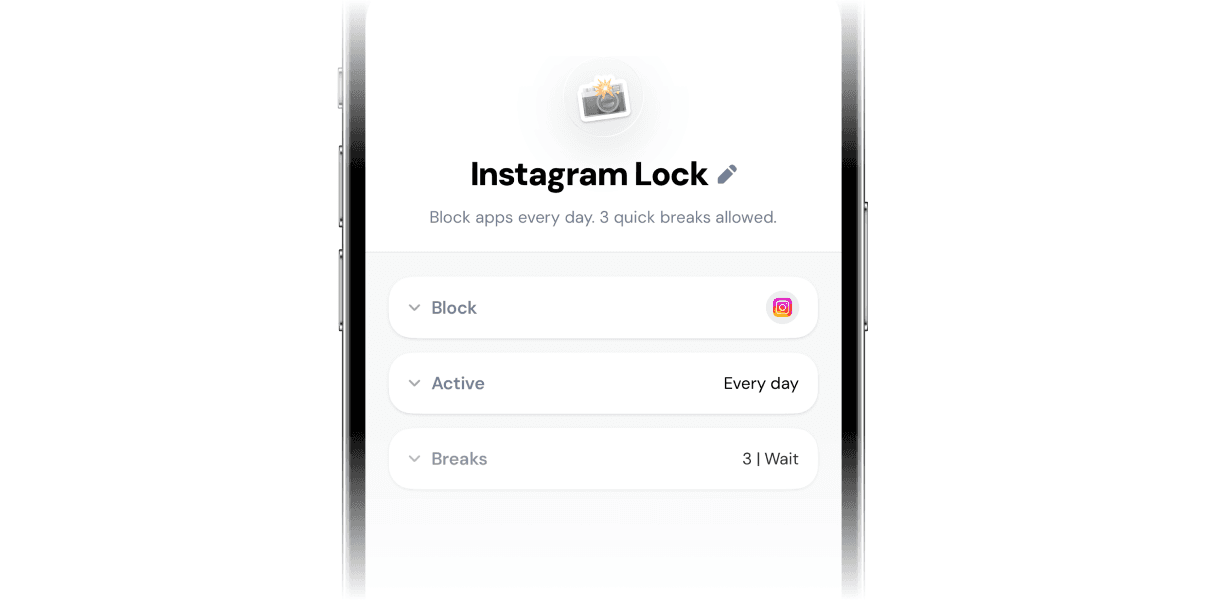

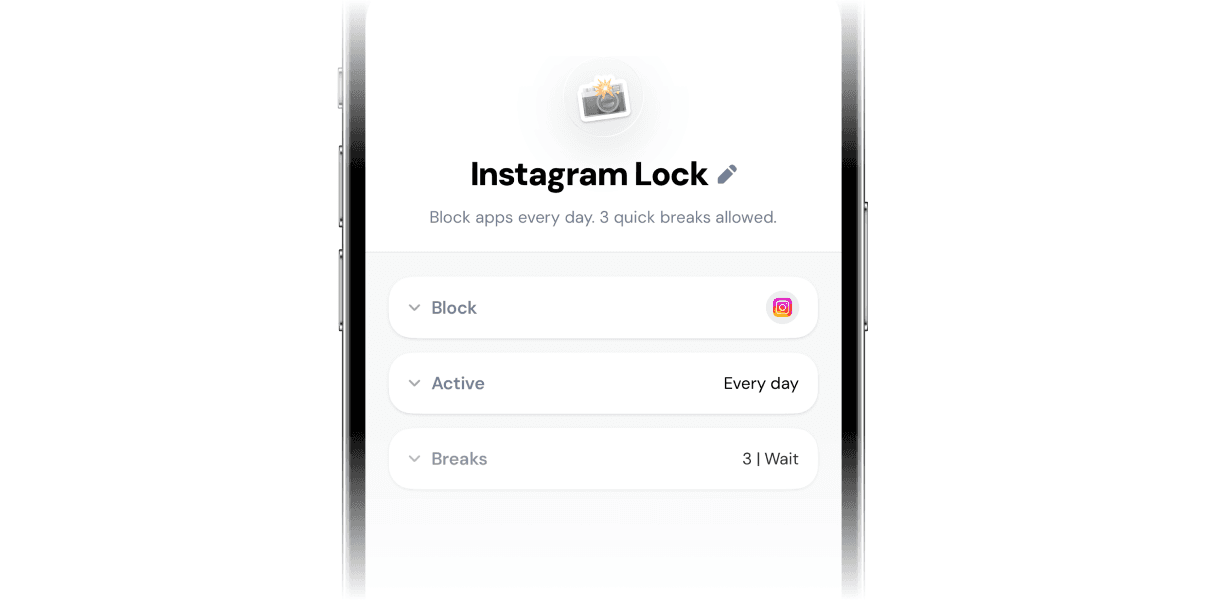

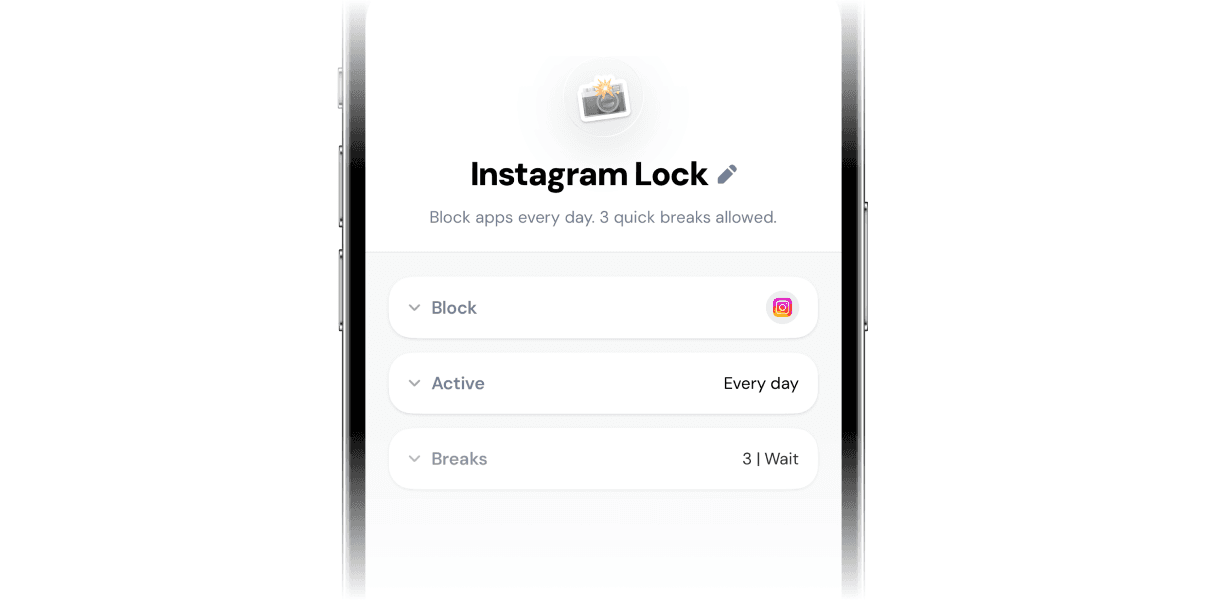

How to setup an opens limit (with friction) instead?

You can replace your time limit with an opens limit in just 2 minutes by following the simple guide below.

Once in the app, go to Rules > + > Recurring session

Choose the distracting apps you want to add friction to

The interesting part happens in the “Breaks” section

Choose the number of breaks (or opens) you want per day. A good rule of thumb is to split your opens into sessions of 5 or 10 minutes maximum. For example, if you want to spend a maximum of 30 minutes on Instagram per day, you can set 3 opens of 10 minutes or 6 opens of 5 minutes.

Choose a quick exercise to complete before each open (the friction): waiting, breathing, writing your reason for using the app, etc. This is where Jomo shines. Use friction that is gentle but consistent.

Between opens, the apps you selected will be blocked, and you won’t receive notifications from them. This is especially useful, as it removes the triggers that often make you want to open them in the first place.

Instagram is blocked by default. 3 opens allowed per day.

Don’t hesitate to start small. You can always reduce the number of allowed opens once you feel more comfortable, or choose a harder form of friction. You’re aiming to reach that sweet spot where either:

You don’t always use all your opens on a given day

When you do reach them, you feel satisfied, with little to no frustration

What actually changes behavior long term is not a stronger wall at the end. It is a better door at the beginning.

A time limit intervenes at the end of the habit. It waits until you are fully engaged, attention captured, brain invested, and then it tries to stop you. That is the worst possible moment to introduce constraint.

The most important shift you can make in 2026 to reduce your screen time is to stop trying to “win” at the end of the habit, and start redesigning what happens before the hook. Instead of letting yourself fall into the app and hoping a time limit will save you later, you create a small pause before each entry, and you turn scrolling into a choice again.

So if time limits have not worked for you, do not conclude that you lack discipline. You probably just tried to solve the habit at the wrong stage.

Thanks for reading so far! If you want to give my app Jomo a try, download it from the App Store and use my code JZ5RP5 to try the Plus plan free for 14 days.

What Works Better Than Time Limits in 2026

If time limits are not optimal, what is? The short answer is: friction and intention. You want to change your screen habit upstream, before it becomes automatic.

Concretely, this means shifting away from “I can use Instagram for 30 minutes a day” and toward:

Limiting the number of openings

Adding a tiny speed bump before each opening

Deciding how long you want to stay before entering

For example:

3 openings per day of Instagram

10 minutes each

with a small action before opening (waiting, breathing, writing your reason for using the app)

Let’s break down why this approach work best.

1. Friction, But At The Right Moment

Friction is one of the most powerful tools in habit design.

In simple terms, friction is effort. The harder something is to do, the less likely it becomes automatic. Over the past decade, phones have removed almost all friction. Your phone is always with you. It unlocks instantly. Apps open in milliseconds. Feeds never end. Notifications pull you in without permission.

So the best way to change a screen habit is to reintroduce small friction at the start of the loop, not at the end.

Instead of blocking you after 30 minutes, you add a small pause before opening the app. That pause can be a decision, a short wait, a breath, a reminder, or a simple question: “Do I actually want to open this right now?”

That moment of friction sounds tiny, but it completely changes the habit. It shifts you from autopilot to agency.

In Jomo, this is one of the core ideas: adding intentional friction before opening distracting apps, rather than only punishing you after you have already fallen into the scroll.

What if you had to recopy this text before opening Instagram? You'd actually think twice about it.

2. Intentional Sessions Instead Of Compulsive Use

Another big shift is moving from compulsive use to intentional sessions.

A lot of screen time is not chosen. It is compulsive. A few minutes here, a few minutes there, repeated all day. It feels harmless because each session is short, but the habit becomes constant.

A healthier screen habit often comes from doing the opposite: fewer openings, more intention.

For example, instead of “I can use Instagram for 30 minutes per day” you move to “I can open Instagram three times per day, and I choose how long each session will be”.

This one change is surprisingly effective because it forces you to be conscious at the exact moment the habit usually runs unconsciously.

Jomo is built to support this style of use. Not just time limits, but intentional sessions and controlled openings, so your screen time habits becomes something you choose, not something that happens to you.

3. Awareness Beats Restriction

The last principle is awareness.

A lot of people think they need stricter rules. What they actually need is better awareness. Not in the form of shame or obsessive tracking, but in the form of small check-ins that make the habit visible again.

When you add friction and intentional entry, awareness shows up naturally. You start noticing patterns: which apps you open when you are stressed, which time of day triggers your worst scrolling habit, which moments are actually fine.

This is how many Jomo users end up reducing screen time. They stop hitting their limits because they are no longer entering apps mindlessly. The habit changes shape before the minutes even matter.

How to setup an opens limit (with friction) instead?

You can replace your time limit with an opens limit in just 2 minutes by following the simple guide below.

Once in the app, go to Rules > + > Recurring session

Choose the distracting apps you want to add friction to

The interesting part happens in the “Breaks” section

Choose the number of breaks (or opens) you want per day. A good rule of thumb is to split your opens into sessions of 5 or 10 minutes maximum. For example, if you want to spend a maximum of 30 minutes on Instagram per day, you can set 3 opens of 10 minutes or 6 opens of 5 minutes.

Choose a quick exercise to complete before each open (the friction): waiting, breathing, writing your reason for using the app, etc. This is where Jomo shines. Use friction that is gentle but consistent.

Between opens, the apps you selected will be blocked, and you won’t receive notifications from them. This is especially useful, as it removes the triggers that often make you want to open them in the first place.

Instagram is blocked by default. 3 opens allowed per day.

Don’t hesitate to start small. You can always reduce the number of allowed opens once you feel more comfortable, or choose a harder form of friction. You’re aiming to reach that sweet spot where either:

You don’t always use all your opens on a given day

When you do reach them, you feel satisfied, with little to no frustration

What actually changes behavior long term is not a stronger wall at the end. It is a better door at the beginning.

A time limit intervenes at the end of the habit. It waits until you are fully engaged, attention captured, brain invested, and then it tries to stop you. That is the worst possible moment to introduce constraint.

The most important shift you can make in 2026 to reduce your screen time is to stop trying to “win” at the end of the habit, and start redesigning what happens before the hook. Instead of letting yourself fall into the app and hoping a time limit will save you later, you create a small pause before each entry, and you turn scrolling into a choice again.

So if time limits have not worked for you, do not conclude that you lack discipline. You probably just tried to solve the habit at the wrong stage.

Thanks for reading so far! If you want to give my app Jomo a try, download it from the App Store and use my code JZ5RP5 to try the Plus plan free for 14 days.

What Works Better Than Time Limits in 2026

If time limits are not optimal, what is? The short answer is: friction and intention. You want to change your screen habit upstream, before it becomes automatic.

Concretely, this means shifting away from “I can use Instagram for 30 minutes a day” and toward:

Limiting the number of openings

Adding a tiny speed bump before each opening

Deciding how long you want to stay before entering

For example:

3 openings per day of Instagram

10 minutes each

with a small action before opening (waiting, breathing, writing your reason for using the app)

Let’s break down why this approach work best.

1. Friction, But At The Right Moment

Friction is one of the most powerful tools in habit design.

In simple terms, friction is effort. The harder something is to do, the less likely it becomes automatic. Over the past decade, phones have removed almost all friction. Your phone is always with you. It unlocks instantly. Apps open in milliseconds. Feeds never end. Notifications pull you in without permission.

So the best way to change a screen habit is to reintroduce small friction at the start of the loop, not at the end.

Instead of blocking you after 30 minutes, you add a small pause before opening the app. That pause can be a decision, a short wait, a breath, a reminder, or a simple question: “Do I actually want to open this right now?”

That moment of friction sounds tiny, but it completely changes the habit. It shifts you from autopilot to agency.

In Jomo, this is one of the core ideas: adding intentional friction before opening distracting apps, rather than only punishing you after you have already fallen into the scroll.

What if you had to recopy this text before opening Instagram? You'd actually think twice about it.

2. Intentional Sessions Instead Of Compulsive Use

Another big shift is moving from compulsive use to intentional sessions.

A lot of screen time is not chosen. It is compulsive. A few minutes here, a few minutes there, repeated all day. It feels harmless because each session is short, but the habit becomes constant.

A healthier screen habit often comes from doing the opposite: fewer openings, more intention.

For example, instead of “I can use Instagram for 30 minutes per day” you move to “I can open Instagram three times per day, and I choose how long each session will be”.

This one change is surprisingly effective because it forces you to be conscious at the exact moment the habit usually runs unconsciously.

Jomo is built to support this style of use. Not just time limits, but intentional sessions and controlled openings, so your screen time habits becomes something you choose, not something that happens to you.

3. Awareness Beats Restriction

The last principle is awareness.

A lot of people think they need stricter rules. What they actually need is better awareness. Not in the form of shame or obsessive tracking, but in the form of small check-ins that make the habit visible again.

When you add friction and intentional entry, awareness shows up naturally. You start noticing patterns: which apps you open when you are stressed, which time of day triggers your worst scrolling habit, which moments are actually fine.

This is how many Jomo users end up reducing screen time. They stop hitting their limits because they are no longer entering apps mindlessly. The habit changes shape before the minutes even matter.

How to setup an opens limit (with friction) instead?

You can replace your time limit with an opens limit in just 2 minutes by following the simple guide below.

Once in the app, go to Rules > + > Recurring session

Choose the distracting apps you want to add friction to

The interesting part happens in the “Breaks” section

Choose the number of breaks (or opens) you want per day. A good rule of thumb is to split your opens into sessions of 5 or 10 minutes maximum. For example, if you want to spend a maximum of 30 minutes on Instagram per day, you can set 3 opens of 10 minutes or 6 opens of 5 minutes.

Choose a quick exercise to complete before each open (the friction): waiting, breathing, writing your reason for using the app, etc. This is where Jomo shines. Use friction that is gentle but consistent.

Between opens, the apps you selected will be blocked, and you won’t receive notifications from them. This is especially useful, as it removes the triggers that often make you want to open them in the first place.

Instagram is blocked by default. 3 opens allowed per day.

Don’t hesitate to start small. You can always reduce the number of allowed opens once you feel more comfortable, or choose a harder form of friction. You’re aiming to reach that sweet spot where either:

You don’t always use all your opens on a given day

When you do reach them, you feel satisfied, with little to no frustration

What actually changes behavior long term is not a stronger wall at the end. It is a better door at the beginning.

A time limit intervenes at the end of the habit. It waits until you are fully engaged, attention captured, brain invested, and then it tries to stop you. That is the worst possible moment to introduce constraint.

The most important shift you can make in 2026 to reduce your screen time is to stop trying to “win” at the end of the habit, and start redesigning what happens before the hook. Instead of letting yourself fall into the app and hoping a time limit will save you later, you create a small pause before each entry, and you turn scrolling into a choice again.

So if time limits have not worked for you, do not conclude that you lack discipline. You probably just tried to solve the habit at the wrong stage.

Thanks for reading so far! If you want to give my app Jomo a try, download it from the App Store and use my code JZ5RP5 to try the Plus plan free for 14 days.

Credits

Photographies and illustrations by Unsplash. Screenshots by Jomo.

Continue reading

Continue reading

The Joy Of Missing Out

Développé en Europe

Tous droits réservés à Jomo SAS, 2025

The Joy Of Missing Out

Développé en Europe

Tous droits réservés à Jomo SAS, 2025

The Joy Of Missing Out

Développé en Europe

Tous droits réservés à Jomo SAS, 2025